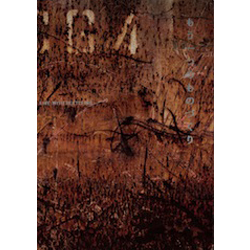

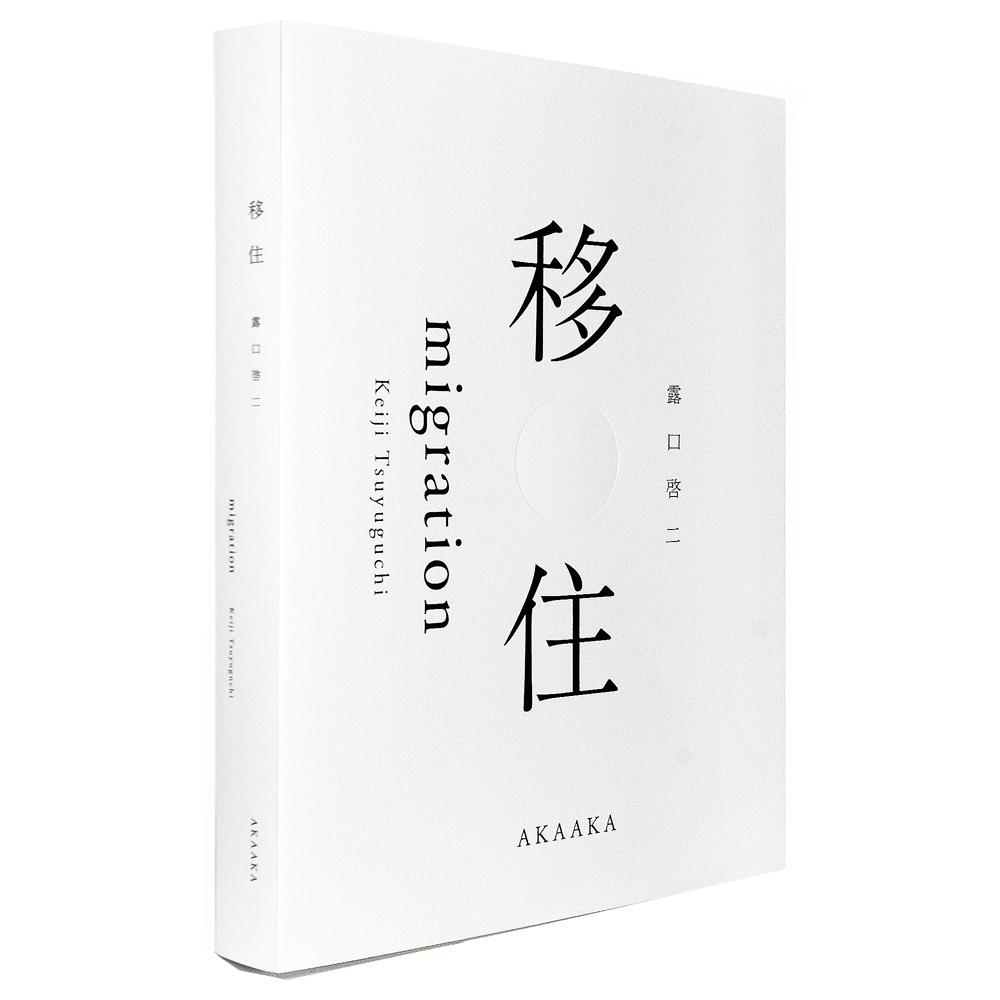

露口啓二『移住』

発行:赤々舎 Size:H298mm × W224mm Page:336 pages Binding:Softcover Published in July 2024 ISBN:978-4-86541-190-4 |

¥ 7,000+tax

国内送料無料! お支払い方法は、PayPal、PayPay、Paidy 銀行振込、郵便振替、クレジットカード支払いよりお選び頂けます。 |

|---|

About Book

諸力によって住むことが排除された、遍在する諸空間──

写らないものと向き合い、見えていなかった地層を探る視覚をもつ

migration

Keiji Tsuyuguchi

An island nation, built upon the framework of modern imperial rule, emerged to the east of the Eurasian continent, separated by the sea. Since its inception, various circumstances have continuously generated people forced into migration. One of the things photography in this book seeks to capture is the juxtaposition between the lands from which displaced individuals originally hailed and the northern islands they migrated to. One such island, dubbed"Hokkaido"by the newly formed nation, was incorporated into the state alongside its indigenous Ainu people and became a target for colonization from the mainland. Simultaneously, numerous forced relocations of the Ainu people became institutionalized.

Additionally, this book primarily focuses on various regions such as parts of the cities Tokyo and Sapporo, where the administrative body known as the"Development Commission,"which was heavily involved in these relocations, was established post-state formation, regions formed by the mining industry now facing decline and extinction, and these various territories are captured through photography.

Located in the heart of Tokyo, the city where the Development Commission was placed and surrounded by various powers constituting the nation's authority, lies the"Imperial Palace,"an invisible space where residing is excluded, and one of the subjects of this book.

On the other hand, in recent years, we have experienced the emergence of highly unique spaces in our archipelago. This includes the formation of the"Difficult-to-Return Zone"and its surrounding areas, contaminated by high levels of radioactive materials due to the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant accident. Once again, people were forced to move from their traditional homes and leave the area.

This attempt to find strong homogeneity between these vastly different spaces in origin, history, and time̶the Difficult-to-Return Zone and the Imperial Palace̶forms another axis of this book.

The forces that gave rise to the Imperial Palace and the Difficult-to-Return Zone continue to create several spaces that appear similar or homogenous to them. These spaces, inherently invisible due to the exclusion of habitation, intersect and overlap with the locations constituting the first axis, appearing in our sight. Therefore, what appears in photographs̶the seemingly visible landscapes, cities, mines, nuclear power plants, farmlands, and the residences of those who live there̶forms part of this book.

These photographs are juxtaposed with timelines of events that occurred in those places and spaces. However, the timelines compiled here are merely arbitrary listings of events selected from existing or perpetually ongoing event descriptions. The photographs taken here merely fix fragments of chance encounters at specific times and places.

Spaces akin to the Imperial Palace and the Difficult-to-Return Zone, with their homogeneity, pervade invisibly. If so, we must resist the rituals that have repeatedly occurred in spaces where habitation is excluded and create and conduct something akin tocounter-rituals, not to remember something, but never to forget. It's about probing our dwelling places with our own "life" perspective, revealing unseen layers, honing our vision to expose the turmoil and chaos.

Contents

017 1 開拓使東京出張所札幌本府 043 2 東京都渋谷区開拓使東京官圍 071 第2章 対雁 来札 二風谷 093 第3章 四国 北海道 095 1 児島村、渋野村 109 2 別子銅山と国領川 125 3 ヨイチ、ソオベツ、オン子ナイ 145 第4章 足尾 谷中 サロマベツ 147 1 足尾銅山 165 2 松木村と谷中村の滅亡 187 3 サロマベツ 201 第5章 東京都世田谷区 拓北農兵隊世田谷部落 227 第6章 夕張 三笠 美唄 247 第7章 福島 249 1 福島原子力発電所事故,避難指示解除区域 266 満州と福島 273 2 福島原子力発電所事故·帰還困難区域 290 双葉町北広町 297 終章 皇居 310 写真史の死角から|倉石信乃 328 犯罪の現場に戻る|鵜飼哲 332 参考文献 | 266 Manchuria and Fukushima |

Related Exhibitons

|

露口啓二「移住」 会期:2024年7月11日(木)〜7月21日(日) 時間:12:00~19:00[木・金・土]/12:00~17:00 [日] 休廊日:月・火・水 トークイベント 四方幸子(キュレーター/批評家) × 露口啓二(写真家) |

|

|

Related text 露口啓二「移住」展に寄せて 四方幸子「移住─現在そして未来を生き抜くために」 |

|

Artist Information

露口啓二

1950年 徳島県生まれ。1990年代末より、北海道の風景と歴史に着目した写真シリーズ「地名」の制作を開始。2014年 第一回札幌国際芸術祭に、映像と写真のインスタレーションを発表。同年、人間の営みの痕跡が自然に浸食されていく様子を撮った「自然史」シリーズの制作を開始。2018年「自然史」シリーズを「今も揺れている」展(横浜市民ギャラリーあざみ野)に出品。同年「地名」シリーズを「さがみはら賞受賞」展出品。2020年「地名」と「自然史」を「道草」展(水戸芸術館現代美術ギャラリー)に出品。2021年「The world began without the human race and it will end without it」展(国立台湾美術館)に出品。2021年より2023年まで、映画『Wakka』に撮影監督として参加。写真集に『自然史』(2017)『地名』(2018)がある。

Keiji Tsuyuguchi

Born 1950 in Tokushima prefecture.

From the end of the 1990s, Keiji Tsuyuguchi started creating the series "Place Names" with an emphasis on the landscape and history of Hokkaido. "The photographer arrived late to the incident," believes Tsuyuguchi, who has attempted to capture the changes that occur in an environment by placing himself within it and repeatedly visiting a location with the aid of historical documents and reference materials, rather than reproducing the results of an incident.

In 2014, Presented a video and photography installation at the Sapporo International Art Festival(SIAF2014). In the same year, started the "On Natural History" series, capturing traces of human activity being eroded by nature. In 2018, Exhibited the "On Natural History" series at the group exhibition "Azamino Contemporary vol.9 Uncertain Landscape" (Yokohama Civic Art Gallery Azamino, Kanagawa). Also, in the same year, exhibited the "Place Names" series at the Exhibition for Sagamihara City Photo Award.

In 2020, Exhibited both "Place Names" and "Natural History" at the group exhibition "Michikusa: Walks with the Unknown "(Contemporary Art Gallery, Art Tower Mito).

In 2021, Exhibited at "The World Began Without the Human Race and It Will End Without It" (National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts).

His major published photobooks include "On Natural History" (2017, AKAAKA) and "Place Names" (2018, AKAAKA).

Related Items

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

|

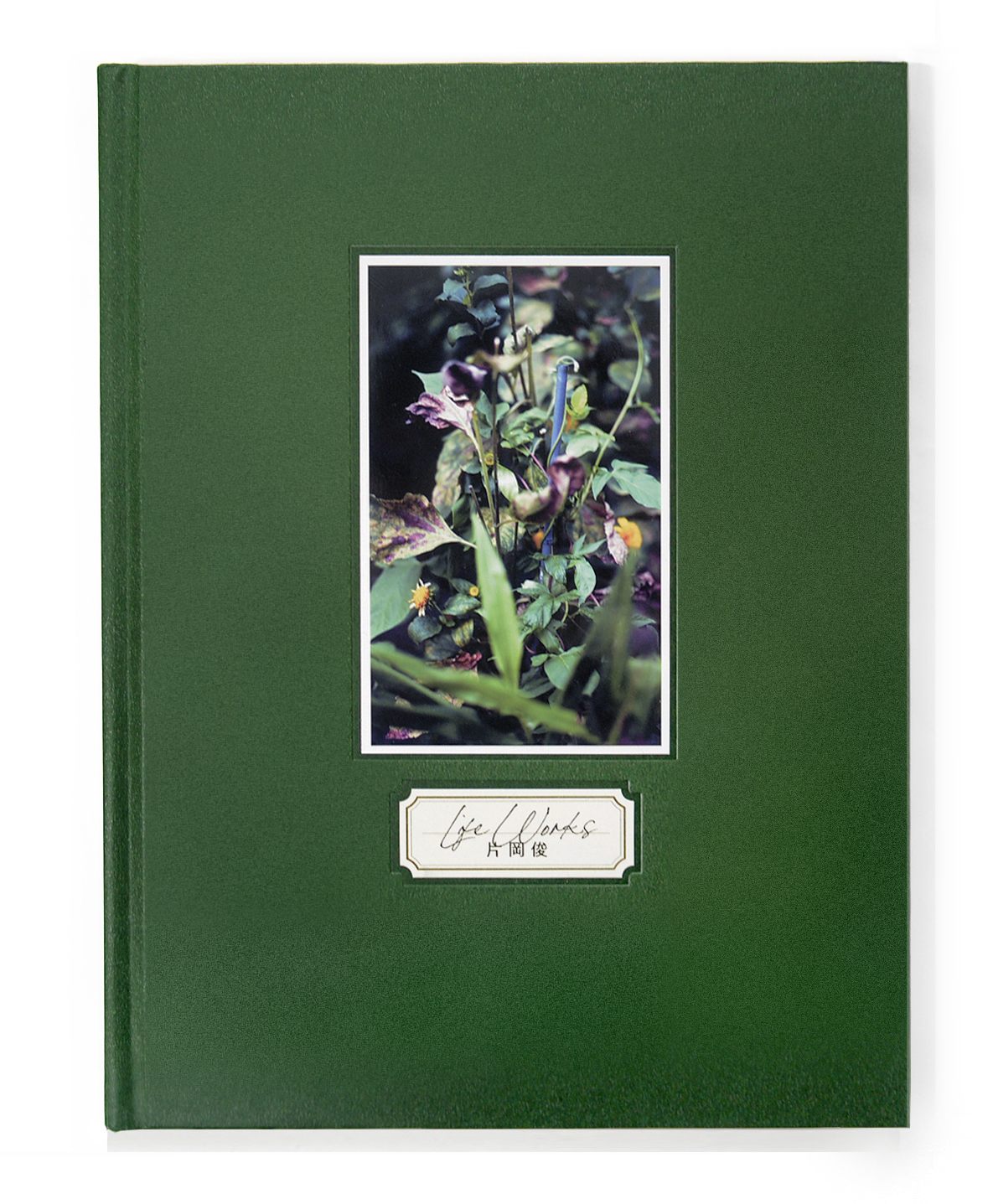

米田知子 『After the Thaw 雪解けのあとに』 (Out of Stock) |

|

|---|