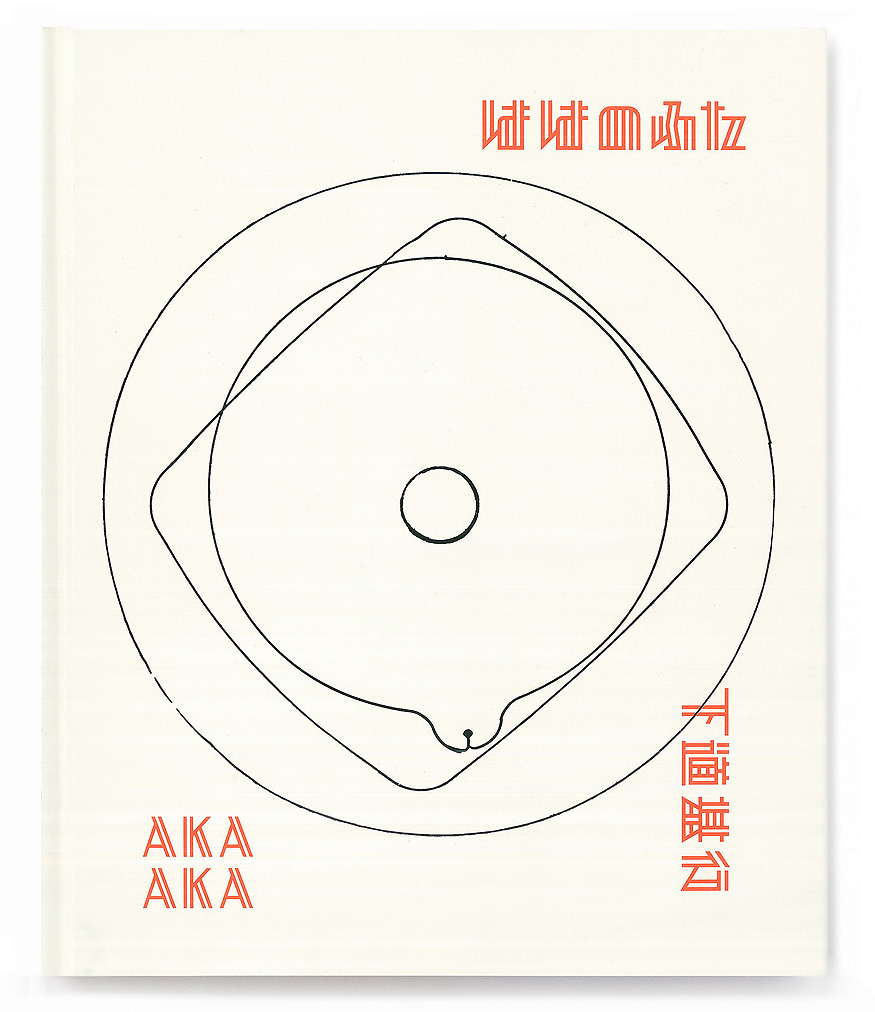

飯沼珠実『JAPAN IN DER DDR ─東ドイツにみつけた三軒の日本の家 』

発行:赤々舎 Size:H257mm x W182mm Page:176 pages Binding:Softcover bilingual (Japanese and German) Published in June 2025 ISBN:978-4-86541-204-8 |

¥ 4,500+tax

国内送料無料! お支払い方法は、PayPal、PayPay、Paidy 銀行振込、郵便振替、クレジットカード支払いよりお選び頂けます。 |

|---|

About Book

「家」の詩学── 人と建築のあいだに宿る記憶と経験

JAPAN IN DER DDR

Tamami Iinuma

Japan in der DDR - Three Japanese Houses Found in East Germany is a project composed of photographs and texts that trace a journey of discovery sparked by Tamami Iinuma's encounter with the still-standing building Interhotel Merkur, Leipzig (now The Westin) in the former East German city of Leipzig, where she unexpectedly arrived in 2008 and lived for approximately six years beginning in 2009.

Shortly after discovering the Merkur, she learned that it was the first European project undertaken by the Japanese company Kajima Corporation. The hotel was one of four large-scale turnkey projects the company carried out in the German Democratic Republic (GDR; in German: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, or DDR) in the late 1970s. The other three projects were the International Trade Center in Berlin, the Interhotel Bellevue in Dresden, and the Grand Hotel in Berlin.

Following these projects, Kajima established a regional headquarters in London, offering comprehensive services--from feasibility studies to actual construction--to Japanese companies expanding into EU countries. Today, the company operates out of offices in Warsaw and Prague and continues to be involved in a wide range of construction projects across Europe.

Among these four buildings, Iinuma chose to focus on the hotels. Her interest stemmed from the theatrical quality of hotels--spaces that often serve as backdrops for films and novels. In addition, while researching materials related to the Merkur, she repeatedly encountered instances where the word "hotel" was used interchangeably with "house." Having long been drawn to the poetics of the "house," she felt an intense pull toward this linguistic and conceptual overlap.

Artist Information

飯沼珠実

1983年、東京都生まれ。2008年から一年間、ライプツィヒ視覚芸術アカデミーに留学、2013年までライプツィヒに在住(2010年度ポーラ美術振興財団在外研修員)。2018年、東京藝術大学大学院美術研究科博士後期課程修了。現在は東京を拠点に活動。主な個展に、「機械とこころ一白くて小さな建築をめぐり」(ニコンサロン、2023)「JAPAN IN DER DDR-東ドイツにみつけた三軒の日本の家」(ニコンサロン、2020)、「建築の瞬間」(ポーラ美術館アトリウムギャラリー、2018)、「建築の建築」(POST、2016)など。主な企画展に、「Von Ferne.Bilder zur DDR」(ヴィラシュトゥック美術館、ミュンヘン、2019)、「Requiemfor a Faild State」(HALLE 14ライプツィヒ現代アートセンター、ライプツィヒ、2018)など。

Tamami Iinuma

Born in Tokyo in 1983. In 2008, she spent a year studying at the Academy of Fine Arts Leipzig (Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst Leipzig), and remained based in Leipzig until 2013. In 2010, she was awarded a fellowship by the Pola Art Foundation for overseas research. She received her Ph.D. from the Graduate School of Fine Arts at Tokyo University of the Arts in 2018. She is currently based in Tokyo.

Her major solo exhibitions include Machine and Heart - On the White, Small Architecture (Nikon Salon, 2023), JAPAN IN DER DDR - Three Japanese Houses Found in East Germany (Nikon Salon, 2020), Momentary Architecture (Pola Museum of Art, Atrium Gallery, 2018), and House of Architecture (POST, 2016).

She has also participated in numerous group exhibitions, including Von Ferne. Bilder zur DDR (Museum Villa Stuck, Munich, 2019) and Requiem for a Failed State (HALLE 14 - Center for Contemporary Art, Leipzig, 2018) .

Related Items

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

米田知子 『After the Thaw 雪解けのあとに』 (Out of Stock) |

古谷誠一 『Aus den Fugen 脱臼した時間』 (Out of Stock) |

古谷誠一 『Memoires 1983』 (Out of Stock) |

|---|